PRESENT DAY SNIPPET: MEMORIES OF MY FATHER

Wishing for a full recovery, longing to hear his voice

Two weeks ago, Michael and I went to visit my Father. From the week prior, he looked absolutely horrendous. His breathing was laboured. He insisted he was fine even though the week before he’d been vomiting blood and he said he hadn’t eaten that day. He later admitted he’d been unwell (without telling us) and he probably hadn’t eaten properly in over eight days, which is worrying for someone who doesn’t have enough body fat to sustain not eating.

I rang 111 and stressed to the operator that I knew what my Father usually looked like and this was not it. He was very ill. They sent an ambulance and the ambulance staff were brilliant. They assessed Father but said that his oxygen saturation was so low, they’d need to take him to hospital. He was not impressed, insisting he’d be okay.

The doctor told us he had a heavy requirement for high-flow oxygen and was severely dehydrated along with having Flu A and pneumonia – and his usual COPD/emphysema. The doctor and nurses wouldn’t commit to his survival. They didn’t know if he’d recover.

As soon as we told his sisters the news, they all rushed to be by his side. Aunty Sheena and Uncle Nick came up from Maldon straight away (almost a five-hour drive) – as did Aunty Jane, Aunty Jeanie, and Uncle Paul, who lived closer. Everyone gathered by Dad’s side, wondering if he’d get better, hoping not to lose him when he’d only been alive seventy years.

But by last week – after having been moved three times in the Huddersfield hospital and twice in the Halifax one – he seemed to be improving. Michael and I saw him Saturday and he was talking but still had barely eaten in his whole stay (being vegetarian and deathly allergic to milk and lactose makes meals difficult). And he’s long lost his appetite over the years, often a worry for us all.

Then, Jae got a dreaded phone call on Saturday night to come quickly to say goodbye. She rang me, incoherent, howling in pain. I too broke down on Michael as I stumbled to get dressed. I was the only one of us who hadn’t had a drink that Saturday night. The drive to the hospital was interminable. The Schrödinger's Cat of life. Would we be able to say goodbye to Father? Would he already be dead when we arrived?

When we got there, I could see his yellow sock poking out, a hospital-issued sock with those grippy soles I’d loved as a child, a sock that wasn’t his. What did it mean if he was lying in bed still? Was it even him?

We weren’t taken to see him. We were ushered into a dark corridor and told to wait for an update from the doctor. Again, our emotions hung in the balance. Was he dead? Dying? What was happening? For over forty-five minutes, hospital staff walked through that corridor, never making eye contact or acknowledging us, making us feel like ghosts in the night. Eventually, I couldn’t stand it and went to the nurses’ station to ask the sister for an update. We just needed to know.

She told us Father had had seizures but was still alive. Shortly after the doctor, “Tom” as he called himself (I’d rather he said Dr So and So), explained what had happened and what they were doing to stabilise him. They stabilised him again but they’d wanted to explain to us how he’d look “much different.” We just wanted to hold his hand and kiss him.

He was sedated yet moaning, noises we couldn’t make out. Oxygen mask affixed to his face again, something he doesn’t tolerate well. We stayed until past 3 am until I had to pry my sister away. We needed sleep and we couldn’t do anything more.

What was worse for me was seeing his face, his eyes moving and trying to focus on something or nothing at all, locked in his head, not knowing that it was us. Seeing his face but knowing he was not there.

Michael and I went on Sunday, seeing Aunty Jane in the lobby. Father was there again, conscious, blinking, but not returned to his body, not able to talk, not able to move his left side – a stroke added to the five seizures.

When Pam, Jae, and I went yesterday on Monday, he could say, “no” and “stop” but I don’t think he knew we were there fully. He was frustrated at having the mask on, at being trapped in himself, at being unable to talk to us, a message he wanted to convey, “I can’t pick it up,” he said to Pam as she was by his bedside and Jae and I had an update from the doctor.

Now, it’s a waiting game again. Will he recover? Will his body respond? Will the feeding tube on the plan help him gain some nourishment and strength from a body that must have been long malnourished?

I’m not ready to lose my Father yet. Jae isn’t either. And his sisters’ love and support show just how much he means to us all.

I hope to the universe that things improve. So much loss and worry in my life is making me feel wrung out like a sponge, with little left to give.

I am waiting to see what happens, to see if he returns to his body, to say goodbye or to celebrate his healing. I long to hear his voice, the comforting voice, calm, reassuring, loving.

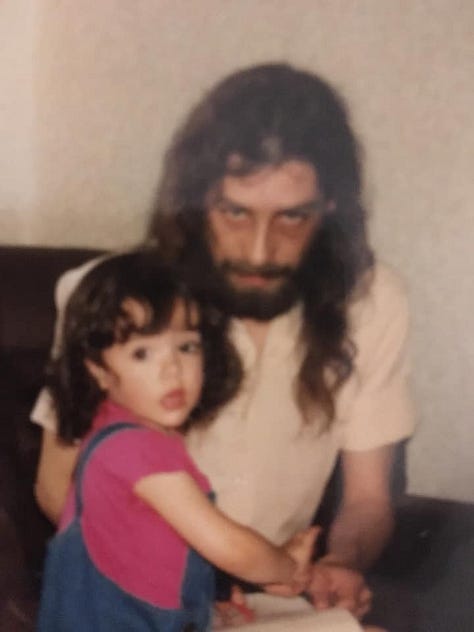

I think one of my Father’s great sadnesses is the time I moved to America. During nights when we’d have a drink together and he’d had a touch too much, he would say how he hadn’t wanted my mother to take me but she was a good mother and he couldn’t stop her. He consoled himself that, educationally, at least the US had turned out to be a better fit for me.

We didn’t see each other for 9 long years. He wrote to me every week when I was gone. I still have the letters. When searching for his things to take to the hospital when he went in the ambulance, I found the letters that I wrote back (certainly not as many) tucked away in a drawer in his bedroom, in a plastic bag that had gone brittle with age.

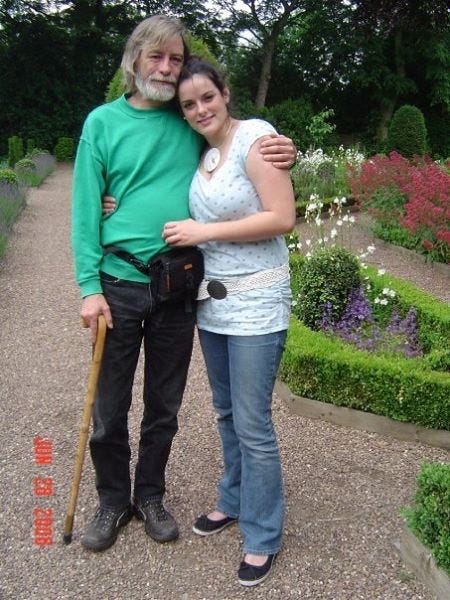

When my first husband left me, I moved to England for a fresh start and to be closer to Dad, my sister, and my niece Caroline – as well as Grammy, Grandad, Grandma Gill, cousins, cousins’ children, etc. But I moved in with Dad and he took me in with no questions asked, no hesitation.

Dad only lives 2.1 miles away from me, a 6-minute drive, and we only go once a week. Life gets busy. We sometimes have game nights (sometimes Cards Against Humanity is interesting when played with parents). We always enjoy going over. We love our chats with Dad – if I can get a word in edgeways with Michael and Dad chatting away as they share many interests.

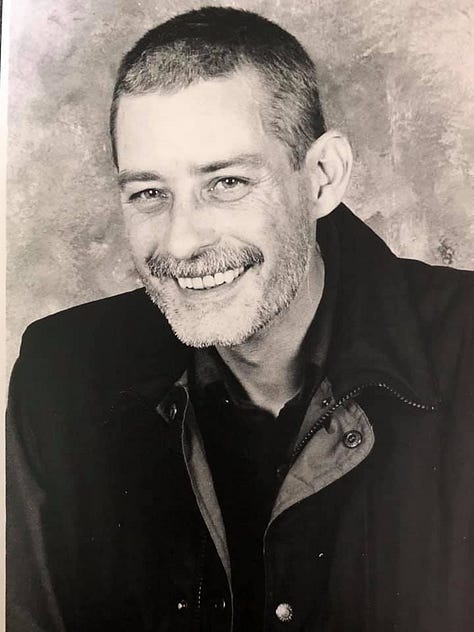

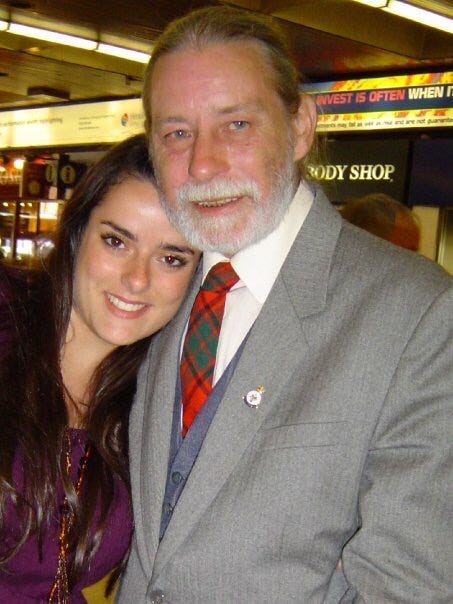

If I get the chance to tell Father, I’d tell him he was and is a wonderful Dad. He’s not the stereotypical father who is under the car, tinkering and fixing, watching sports (but I think he does support City), putting up shelves, reclining and watching television. He was always more the intellectual sort. He’d sit in his chair reading. He was more there for cuddles and chats, art and sport. In his younger years, he was a carpenter, doing antique furniture restoration, often of the Georgian era.

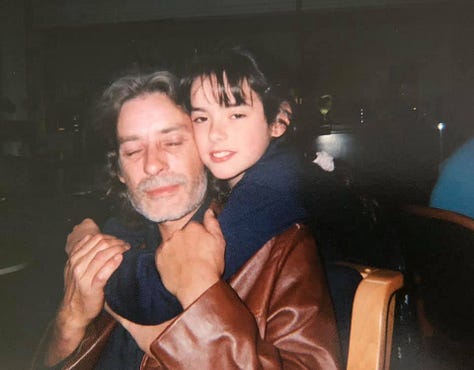

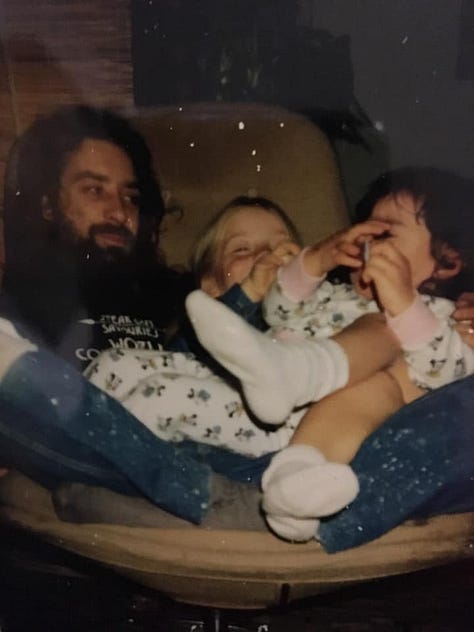

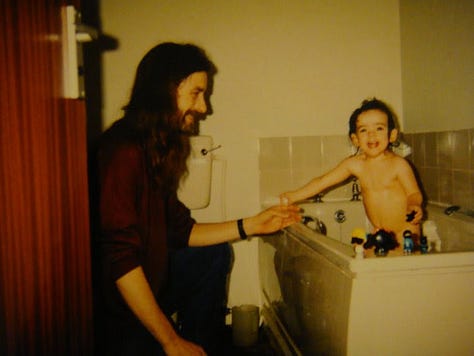

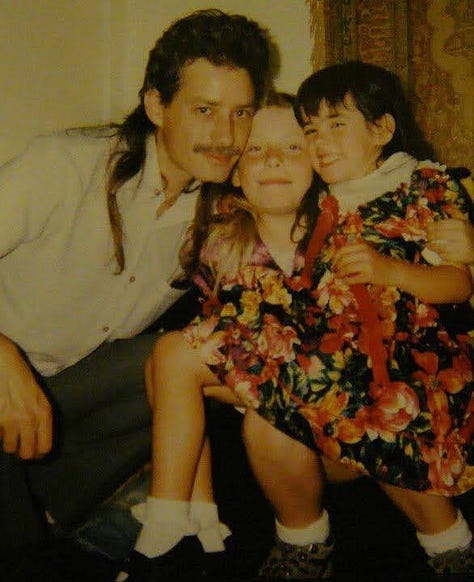

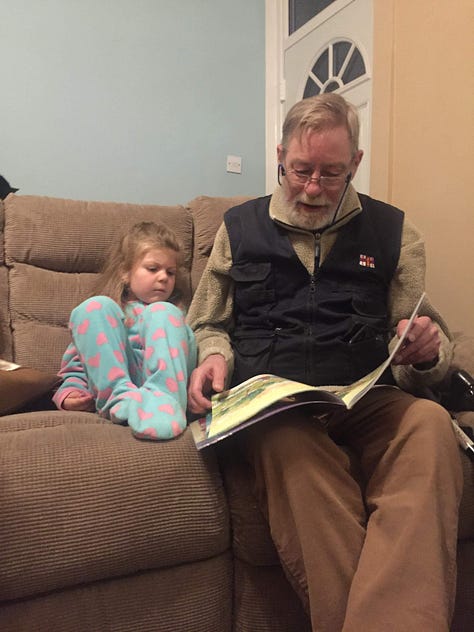

When I was young, he was game to hold my hand and skip down the street, often embarrassing my sister who is five years older and was too cool for skipping. We’d go to the library every weekend together. Books were always a vital part of our lives. We’d play badminton together. We’d do art projects like painting or papier mache (we once made money box pigs using a balloon and egg carton pieces).

I have nothing but fond amazing memories of my father in childhood. I’d pretend to fall asleep so he’d carry me up to bed on some nights. Other nights, he’d sing to me (often "Kum ba yah") or read me stories. We’d watch Audrey Hepburn films together on his black-and-white television. TV was never a big feature in our houses (Dad’s or Mum’s).

He’d make a massive pot of lentil and dumpling stew because he knew my appetite was always voracious and could run to five bowls. If Jae had eaten all the salt and vinegar crisps, he’d put vinegar on the ready-salted ones for me, even though they’d go a little soggy. I was also prone to theatrics and he’d watch the one-girl “plays” I’d put on for him and Jan (his long-time partner at the time) as well as my “ballet” shows.

I don’t remember a raised voice or a telling-off ever. He always had a calm and relaxed temperament. He always radiated love.

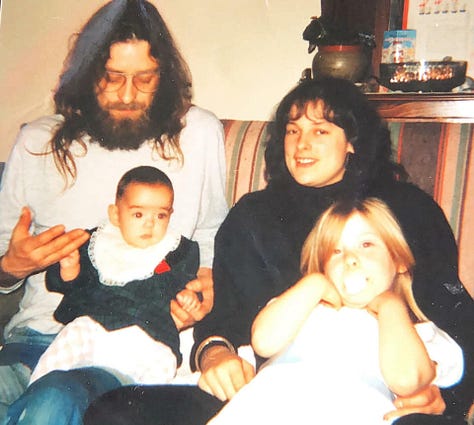

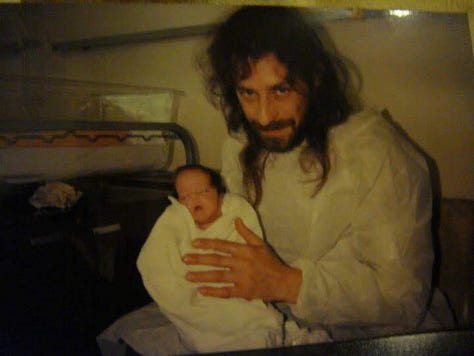

I was an “accident” child. My parents barely dated yet they loved me and each other. They were always friends. I never wished they were together. They were too different in temperament. I didn’t grow up in a traditional two-parent household but I didn’t grow up without love. I had a wider support network that mattered. I had all of these people around me who meant so much to me – from my parents to my uncles to my grandparents to the Leylands. Maybe that lifestyle is a little too bohemian for some but it worked out okay for us. I had what I needed materially and I especially had love.

When Father moved to Todmorden next door to Jae’s mother (Jae and I have different mothers) and her husband, they’d hear Dad and Liz laughing through the walls. When Liz died of lung cancer over a decade ago, Dad struggled without her. He didn’t take as good care of himself as he ought to since it was difficult with his rare genetic condition too (familial/hereditary spastic paraplegia) which left him in chronic pain and often confined him to a wheelchair. Yet he maintained his independence and good spirits as much as possible.

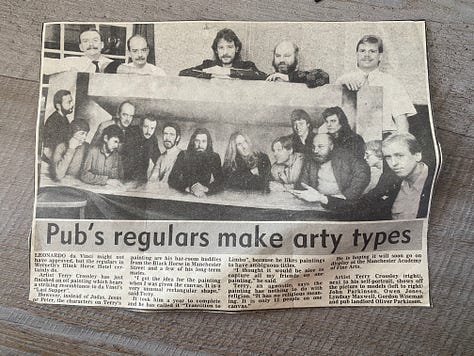

He had lived life to the full in his youth and he was known for his welcoming spirit and generosity. He threw many parties in the 80s and 90s and people knew they were always welcome and they’d always be fed. Pop in some more lentils and potatoes and things can stretch!

People often celebrate others with traditional success markers but Father devoted his life to raising Jaelithe; his girls were always top priority. Later, his disability defined his life but he always retained his intelligence, laughter, and interesting conversation. He was always just there for us. He never lectured or judged our lives. We were free to do as we wanted and we were always loved. He is a man with a good heart, kind, funny, friendly, fun-loving, well-liked, and generous. Father never had grand plans. He was happy with a simple life, a life of enough, a life of reading, his daughters, love, and laughter. What more can you ask for really?

If I get the chance, I will tell Father that he was wonderful, what I needed. He was enough. The way he loves us unconditionally. He’d often joke and say, “My daughters are perfect” in the way only a father can see only the rosy version of us, true or not.